Tags

Bertold Brecht, Louis Armstrong, Mack the Knife, Mackie Messer, Sir Robert Walpole, Threepenny Opera

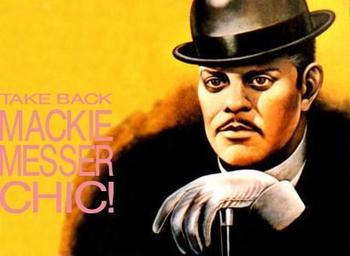

Like most people, I had at best a vague idea that the song “Mack the Knife” had a history before Bobby Darin made his wildly popular recording in the late 1950’s. As enjoyable as I found the song, its pairing of Darin’s breezy, hip singing with the tale of an amoral murderer always puzzled me. The song was originally written in 1928 by Kurt Weill for Bertold Brecht’s play “Drei Gröschen Oper” (Threepenny Opera) – and very much at the last minute for the star, Harold Paulsen, who demanded a song that would help to introduce his character, Mackie Messer (Mack the Knife). This character was based on the charming thief, “Macheath,” from John Gay’s 1728 ballad opera “The Beggar’s Opera” who was in turn thought to be based on Jack Sheppard or even Sir Robert Walpole. In fairness to both of these men, Mack the Knife is amoral, sinister and violent – in addition to having some charm – and more of a modern anti-hero.

The song, in its original conception, was quite deliberately based upon a Medieval murder ballad, a Morität. (mori = death, tät = deed) which would have been sung by strolling minstrels. Here is an early version of the song sung by the playwright himself, Bertold Brecht. This would have been very close to the original version in the play. Aside from Brecht’s thin, reedy voice and his (to our American ears) annoying, rolled “r’s,” this has the feel of the simple folk ballad that it was originally meant to be.

The basic form of the song is only sixteen measures in length – half the length of a typical popular song – however, due to the placement of beat stresses in the first few iterations, it initially sounds like it is only an eight-measure song. It is the repetition of these short units, sung in a rather non-demonstrative, objective manner that gives the song the feel of a traditional ballad – even if it does use a modern chord progression. It is an hieratic account of a doer of great deeds (albeit immoral ones).

The song remained unknown for the most part to American audiences until “Threepenny Opera” played Off-Broadway beginning in 1954, employing an English translation by Marc Blitzstein. However it was a 1956 recording by Louis Armstrong and His All-Stars that really began to bring the song into the American consciousness. I present below a newsreel of a live performance of the song by Armstrong and his combo in London during a 1956 concert tour. We have the beginning of the transformation of the song, in this case into a Dixieland tune. However, for some reason, it doesn’t seem inappropriate to me. Notice that, after the drum solo at the end, the entire piece is shifted up a half-step enabling Ol’ Satchmo to end on a high Bb, but also foreshadowing an even more extensive transformation of the song.

Of course the most familiar – the iconic – version of “Mack the Knife” is the one recorded by Bobby Darin in 1959. At least this is the version that most people over forty would know, and quite a few under forty, as it has continued to be played in many venues for decades. It held the number one position on the Billboard Hot 100 Chart and won Darin a Grammy Award for Best Record in 1959. Possibly the only serious competition that it has had in recent years has been Michael Bublé’s 2004 version. However, Bublé’s version has such a spiritual kinship to Darin’s that it might be described as the version Darin would have recorded on a day when he had even more cocky self-assurance.

Arguably, Bublé out-Darins Darin in his retro-channeling of the Vegas Rat-Pack Era circa 1960. He is Bobby Darin on steroids.

Darin’s version was the most profound transformation of the song that had yet occurred. It became the personal expression of a young hipster – originally a rocker – who was bridging the generation gap between the cocky, curled-lip kiddie-pop of Elvis and the glitzy glamour of the Vegas-oriented adult-pop of the Rat Pack. And the superficial excitement of Vegas is perfectly captured in the constant modulation up a half-step every sixteen measures. It seems to say, “See the flashing lights on the Vegas strip, something exciting is happening! It’s just around the corner!” Although we are not quite sure what it is. Or what it has to do with murder.

Even in its day, the disconnect between the lyrics and Bobby Darin’s interpretation seems to have been, at least vaguely, recognized. Somewhere out there in YouTube Land I came across a delightful clip of Pearl Bailey trying to explain the popularity of the song to Dinah Shore. She says something like, “Well, Honey Child, the people plays that record over and over . . . um . . . because they’s trying to figure out what it all means!” I suppose that if I was a left-wing social critic I would come up with explanations like: 1) it was a Cold War Era Freudian Slip by a society in denial, or 2) that it was representative of a shallow, commercial-driven society masking violent anti-social impulses. Since I try not to take myself too seriously, am not left-wing, and am a music critic, my tentative explanation is that it was the beginning of the trivialization of lyrics in American popular music.

It was arguably the beginning of the phenomenon whereby people like a song because it has a catchy melody, or a beat, etc. but don’t have the faintest idea what the lyrics mean – if they can even understand them – and don’t really care.

To bolster this, I recently came across a charming clip on YouTube in which a young, teenaged Ann Margaret sings “Mack the Knife” in 1961 as part of her screen test, presumably for “Bye Bye Birdie.” I must say that this is the most girly, flirtatious version of a song about the exploits of a murderer that I will probably ever see. In other words, it was just a “cool song” to her and her fellow teenagers of that era as well as a vehicle for the display (or perhaps over display!) of her personality – nothing more.

The final version of “Mack the Knife” which I will discuss is Lyle Lovett’s which appeared on the soundtrack of the 1994 movie, “Quiz Show.” This version brings us full-circle and serves as a summation of the song’s interpretive history. Its more somber mood, brought on by a slower tempo and, initially, a lack of modulation, returns the song to its roots as a true Morität. Another thing that helps is the newer English translation of Ralph Manheim and John Willet that includes some truly creepy lyrics about Mack being an arsonist and a child molester (as well as the murderer which we already knew about). These verses were in the original 1928 German version, but excised in the version performed by Armstrong and Darin in the 1950’s.

In the middle of Lyle Lovett’s version, the tempo shifts somewhat with a walking bass line and a jazzy, muted trumpet solo, as if to acknowledge the Armstrong version. However, it is acknowledged and then incorporated into the overall somber mood of the piece. Later, half-step modulations are employed, seemingly to acknowledge the Darin version, but there is still a pall cast over the mood of the piece by the rest of the accompaniment. The feel of the piece never even comes close to taking on the happy-go-lucky feel of the Bobby Darin version.

In conclusion, though there have been many other singers who have recorded the song, I will only mention three noteworthy ones. Ella Fitzgerald recorded a version in 1960 which includes some of her truly superb scat singing. Sting has performed a version using the original arrangement from the 1928 play and, sadly, Frank Sinatra recorded a rather lackluster version in 1984 on his album “LA Is My Lady.” He sings it to a superb arrangement by Quincy Jones and employs some of the best jazz musicians of the era, but Ol’ Blue Eyes just doesn’t seem to have it anymore. He sings all of the right notes, but that famous Sinatra sense of phrase and timing – which he had well into the 1960’s – seems to be gone.

It is if he is no longer Frank Sinatra but someone’s “Uncle Frank,” singing at his niece’s wedding reception. He’s good, but hardly “The Voice” anymore. Here’s a live version which is close to the recording.

Too bad.